The History of Marrakech

It might be tempting to get lost on Google Maps as you walk the medina’s labyrinthine streets, but looking up – and around – will reveal almost a thousand years of history. While Neolithic remains have been found in the area around Marrakech, the city’s story as we know it starts in 1070 when Almoravid warrior Abu Bakr ibn Umar crossed the Atlas Mountains and arrived on the dusty Haouz plain.

The Almoravids were an Amazigh dynasty who ruled an empire stretching from the Sahara in the south, Senegal in the West, and Spain and Portugal to the north. In search of a permanent capital, they needed hospitable land and soon realised the new area was rich in water. In the shadow of the Atlas Mountains, the Almoravids decided to create the power centre of their empire.

The new city would be named Marrakech. The exact meaning of the name is still debated today. But one possible origin is from the Amazigh words ‘amur akush’ which mean ‘Land of God’.

What started life as a desert encampment however, rapidly expanded as a trading centre. Coins were minted, gold and silver brought to the new city to be traded. Craftsmen from Andalucia and other parts of Africa also travelled to Morocco to work on buildings and monuments – and created a unique fusion of Spanish, Saharan and West African decorative influences.

Soon the city’s first mosque was also built, but it was the construction of Ben Youssef Mosque in the early twelfth century that really kickstarted the growth of the souk as we know it today. New Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf oversaw the building of Ben Youssef and also, crucially, implemented a system of waterworks. Soon more and more artisans were drawn to the city. Four huge new gates were built, followed by a nineteen-kilometre wall built around the circumference of the medina to protect it. The water also allowed gardens to be established – both within personal homes in the medina, but also outside the city walls.

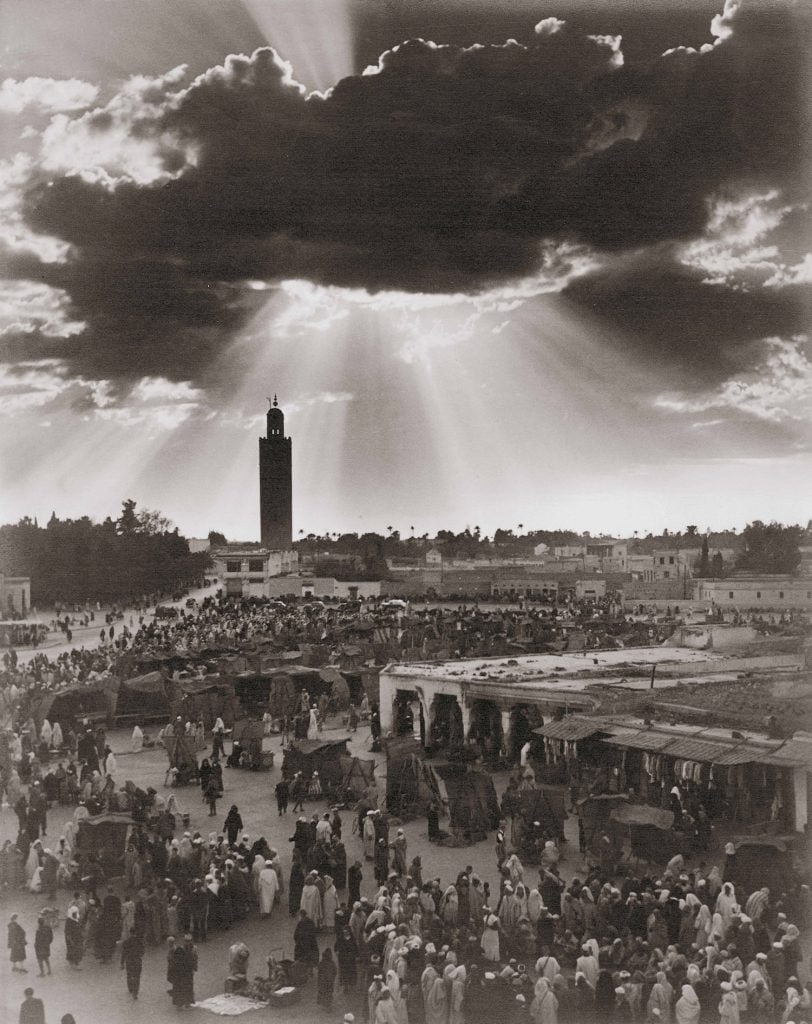

By now, Marrakech was a cultural, religious and trading centre for both North and sub-Saharan Africa – Jemaa el Fna, a thriving kaleidoscope of goods, languages and cultures. But even as Marrakech thrived, disputes within the Almoravid dynasty began to weaken it. And in 1130 the city was attacked by a new dynasty keen to take over this prize.

The first attack by the Almohads – a rival Amazigh tribal confederation – was unsuccessful thanks to the city walls. But after conquering the rest of Morocco, the Almohads returned to Marrakech in April 1147. They scaled the walls, opened the gates and seized the city. Keen to establish their dominance, the Almohads razed the city’s mosques – including Ben Youssef – and started to build the Koutoubia.

For unknown reasons, the Almohad caliph Abd al-Mu’min would later build a second Koutoubia Mosque and leave the first to fall into ruin. Abd al-Mu’min did not live to see the completion of the new – and permanent – Koutoubia but it remains the most famous landmark in Marrakech to this day.

Once again, water was key to the development of Marrakech and the Almohads extended the city’s water system to allow two huge gardens with water basins – Menara and Agdal – to be built. They also enlarged the royal citadel in the Kasbah area to the south of the Koutoubia.

But history repeated itself when Almohads were weakened. And a new dynasty – the Marinids – took power in the early thirteenth century. Soon the influence of Marrakech began to wane as the capital was moved to Fez. It took another 250 years for the city to become ascendant again thanks to the Saadian dynasty who saved it from years of Portuguese attack and reinvigorated the weakened city’s fortunes.

For the Saadians, Marrakech became the focus for the physical – and visual – expression of their power in the form of monuments. They further developed the Kasbah area of the medina and built their famous tombs. In the mid-1500s, they also constructed Ben Youssef Medersa, one of the largest theological colleges in North Africa, and still today a worldwide symbol of the beauty of Arabic design and craft.

Marrakech was never again capital but the city continued to exert its influence.

Two hundred years later, the Alaouite dynasty ascended to power in Morocco and today the 23rd generation of this dynasty, King Mohammed VI, sits on the throne. While the dynasty chose Fez, then Meknes and finally Rabat as their political capital, key courtiers and officials remained in the Marrakech medina and buildings such as the Bahia Palace and Dar Si Said were built. Marrakech continued to evolve, its status as a cornerstone of Moroccan identity undimmed.

Colonial expansion had a profound effect on Marrakech. During the French Protectorate, which lasted from 1912 until 1956, the ‘new town’ of Gueliz was built. Today the majority of art deco villas that were built as homes have been razed but look carefully and you can still find some original buildings.

Nothing however will ever replace the medina as the beating heart of Marrakech. And UNESCO recognised this in 1985 when it was listed as a world heritage site. And still, history and culture continue to fascinatingly collide with the present there every day.

THE CULTURAL HISTORY OF MARRAKECH

All streets in the medina lead back to Jemaa el Fna. And for good reason. Because for centuries, traders from Europe and sub-Saharan Africa met there to buy and sell goods. And with them came a kaleidoscope of culture: storytellers, poets and fortune-tellers; musicians, dancers and snake charmers. Put it all together, and Jemaa was – and still is – the energetic epicentre of Marrakech.

Such is its contribution to the spirit of this city, UNESCO put Jemaa el Fna on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008. And it’s this unique blend – Jemaa el Fna, the souk and medina – that has always drawn travellers, creatives and thinkers here. In 1939, George Orwell published an essay ‘Marrakech’, Winston Churchill described the city as ‘the nicest place on earth to spend an afternoon’ and Hitchcock filmed part of 1956’s The Man Who Knew Too Much in the city.

But the modern fascination with Marrakech was sparked in the 1960s when the medina became synonymous in the popular imagination as a place of experimentation, style and bohemia.

MICK JAGGER, MARRAKECH, 1967 BY CECIL BEATON ©THE CECIL BEATON STUDIO ARCHIVE AT SOTHEBY’S

First came the Rolling Stones in 1967 – shot poolside and on a medina rooftop by Cecil Beaton. The now infamous trip to Marrakech saw the band imploding with the start of the relationship between Anita Pallenberg and Keith Richards – and Brian Jones’ heartbreak.

Two years later, Crosby, Stills and Nash released ‘Marrakech Express’ – inspired by Graham Nash’s trip to Morocco in 1966.

But perhaps the most iconic representation of that time is the famous Patrick Lichfield photograph of Talitha Getty. Wearing harem pants and an embroidered kaftan, she crouches on a medina rooftop with her husband John Paul Getty standing behind her hooded in a djellaba, the Koutoubia rising in the distance. Over the next two years, Lichfield shot successive portraits of Getty in Marrakech.

Print purchasable from CondeNast Store

But she wasn’t the only style icon who’d fallen in love with the city. Algerian-born Yves Saint Laurent was so captivated by Marrakech on his first visit in 1966 that he and partner Pierre Berger bought a house in the medina.

Dar el-Hanch means ‘Snake’s House’ and Saint Laurent painted a snake on the dining room wall of his home that is still there today. Ever after, it continued to appear as a constant motif throughout his work. But what was it that entranced Saint Laurent so much that Marrakech became central to his personal and professional life ever after?

‘Once I grew sensitive to light and colours, I especially noticed the light on colours,’ he once said. ‘On every street corner in Marrakech, you encounter astonishingly vivid groups of men and women, which stand out in a blend of pink, blue, green and purple kaftans.’

It’s something that still captivates visitors to the medina today. In recent years, it’s been spruced up and modernised with an extensive programme of renovation. But nothing can take away that light. The medina of Marrakech was, is, and always will be a living – and working – testament to the history, culture and vibrancy of Morocco.